The liminal space of Marlon Williams

With a new documentary, and album, he's the man of the hour, and everyone and their dog (including me!) wrote about the nation's Ōhinehou obsession this week.

Crust is a weekly newsletter on taste and culture from Tāmaki Makaurau.

Hello, it’s a Marlon-heavy edition today (he so nice and the movie’s so good, I couldn’t help it) and we’re looking at his mythology and malleability here, the work of visualising stardom in 2025, as well as image-making in a more traditional sense — art. I also fan-cast Breakfast at Tiffany’s, tell you what I’ve been up to, and share some trivia about Sophia Coppola and Jane Campion. But first, let’s start on Queen Street.

The rain outside was steaming up the Civic Theatre foyer on Tuesday night when Marlon Williams slouched in, his jetlag slicked back and covered in houndstooth and that famous charm. He looked every bit the star, working the press line. ‘MW’ is writ on his bolo tie, a custom piece he told me. There was “a nice little Crane Brothers houndstooth number”, pants by Workshop (Karen Inderbitzen-Waller dressed him) with those ever-present Dr Martens (low-top always) and, on his right earlobe, a poanamu from his mother.

He’s always a fun interview. This was our third, a brief one, at the world premiere of new film, Ngā Ao E Rua – Two Worlds, which is out now and all about him. You don’t do that every day. He seemed calm, cool as ever, but under the surface, it was another matter. “I’m churning inside.” Being the subject of a documentary is “a different buzz” to his usual creative output. “It’s not something I ever wanted or craved in my life,” he explains, but director Ursula Grace Williams (no relation) convinced him it was a story worth telling. “I’m proud of what it is. But yeah, it’s scary.”

Ngā Ao E Rua is a companion piece to Te Whare Tīwekaweka, tracking its making and Marlon’s life for four years. Ursula’s feature film debut, it follows the creation of the new album, itself a labour of love and learning.

It’s his first fully te reo album — dedicated to the late, great Hirini Melbourne — and it’s a body of work Marlon describes as flawed, naive and brave. New Zealand music press are calling it “a career best”, beautiful and important (I agree) and “the album we’ve all been waiting for”.

Its release is also significant and serendipitous; not lost on anyone is the socio-political climate it was birthed into — launched amidst debate about the Treaty Principles Bill and what’s been called a “pivotal” year for Maori-Crown relations. “It was always going to be something, to stand against the New Zealand political backdrop in some way, but for sure things are way more heightened than I would have predicted,” Marlon tells me. “I was partially prepared.”

He’s spoken about reconnecting with Māoritanga the past few years and weaving it into his music, but this new record is something definitive. It sees him writing in te reo for the first time, and much of the doco shows the labouring that went into it, working with artist, academic and co-writer Kommi Tamati-Eliffe (Ngāi Tahu, Te Atiawa) over lyrics, pronunciation and all those little, important, nuances of the language.

Counterweight to the introspection of the writing process, the film also gives us Marlon the performer, and the reality of touring, something he’d been doing it more or less non-stop for a decade. (His next one starts May 9). Tour life is one of liminal spaces — planes and vans, hotels and green rooms backstage — and some people lose themselves in it if they’re not careful. Artists are collateral damage for their own work. “Touring is really borrowing against the bank. It's constantly making withdrawals,” Marlon says in the film, which, while not sensationalising life on the road (they don’t need to) gives us moving glimpses of how touring takes its pound of flesh.

They also demonstrate restraint. It doesn’t give us everything, nor should it (though we do see a very intimate foot moment). Ursula’s film is observational, free from talking heads and to-camera sit-downs, yet not quite fly-on-the-wall either. It’s about “the spaces in between”, she said, and Ngā Ao E Rua explores that splitness with a gentle touch. We get the serious and the silly, the rock star and the son, and there’s a sense of tightrope walking between public and private personas.

It’s that liminality that makes Marlon so interesting. If you want to read about the nuts and bolts of the documentary I’ll direct you stories by Alex and Coco or Steph and Mitch, because I want to talk about the mythmaking and multiplicity of Marlon Williams.

This current Marlon is everywhere. (Marketing any project, let alone two at once, is a huge job). His latest record Te Whare Tīwekaweka is arguably the finest one he’s made yet, and I challenge you to listen to it and not feel something. Released in April, a week later it was the number one album in Aotearoa, ahead of Sabrina Carpenter and Ariana Grande (last year only two local artists made it to the top spot, DARTZ and L.A.B).

Te Whare Tīwekaweka is new but feels like it isn’t, rather like it’s always been there, existing between the past and present. Unsurprisingly Marlon’s been submerging himself in nostalgia. “The album I’ve been listening to non-stop for the last five years, since before this all started, is The Maniapoto Voices,” he told me. “Four sisters, one guitar, a bass. I’ve said it before, but it should be like the Edmonds Cook Book; it should be in every Kiwi home.”

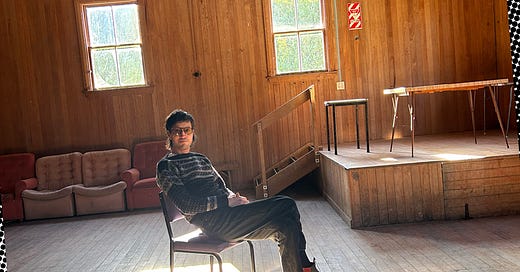

You get the feeling he’s been looking for a sense of grounding, home, what that looks like and how one fits back in. In Ngā Ao E Rua we see him back in Ōhinehou Lyttleton, at Tōrere Marae, and a beautiful old hall in Haast where the album was recorded (where better to make music?). The buildings of the film are their own kind of local mythology, shot tenderly by director of photography Tim Flower, who has steeped the film in golden hour and that great southern light. (If you’ve ever fantasised about retreating to a board-and-batten house in the South Island, then there’s plenty of fodder for you in this film).

There’s a shuffling domesticity and human clutter to the film’s domestic spaces, and with Te Whare Tīwekaweka translating to ‘a messy house’, that sense of living carries weight. In one cottage, Marlon and his mum cook tītī while he talks through his family and fantasies. “I’ve spent a lot of my life creating brothers and sisters for myself.” An only child of parents who separated, his mother Jennifer Rendall (Ngāi Tahu) and father David Williams (Ngāi Tai), both artists, loom large, even though their actual screen presence is quiet and spare. Their appearances, and the way he talks about them, are some of the most poignant of the film. And we all know families are their own kind of mythmaking too.

Jennifer drew the illustration used for the album’s cover art while pregnant with her son. He was born in a bathtub (Boh Runga’s) at a Cashel Street flat and they named him after Brando, the mythology goes. He got into Bob Dylan before plunging into country music as a teenage choirboy in Christchurch. (We know that city cares about what school you went to and his was Christchurch Boys High). Then he was part of that Lyttleton music scene, before he left for Melbourne and beyond.

There’s been so much ink spilled over Marlon Williams — he makes a good profile, all that local lore, and that charisma — and his many awards and albums. My Boy won him Best Solo Artist at the Aotearoa Music Awards last year, and Make Way For Love has become something of a local legend — a breakup record that made a guarded relationship public and brought the pair back together, if only for a song, ‘Nobody Gets What They Want Anymore’, and one recorded on other sides of the world at that.

Aldous Harding is in the documentary, a lot of his musical collaborators are. It spans four years of his life. That’s a long time, particularly as you leave your twenties; so much changes, but a lot doesn’t too. He acknowledged as much with that signature charm and humour, telling the Civic audience — which included everyone from Jon Toogood to Madeleine Sami — how weird it was to show your girlfriend (Melbourne musician Georgia Knight) a movie made before her. Two worlds indeed. You know you’re at a Kiwi premiere when the words buzz and buzzy have been dropped at least three times before the title card rolls.

Being the subject of a documentary is a departure from his screen work to date. I have to confess I forgot all about his appearance in A Star is Born — Bradley Cooper saw him playing at the Troubadour, a scouting itself made from Hollywood mythology — though my favourite film of his is True History of the Kelly Gang, a brutal colonial fever dream that’s underrated (Thomasin McKenzie’s in it too). He played the unsavoury American cowboy George King, and it’s an example of that out-of-time quality Marlon has — that familiar, chiselled face that’s so hard to carbon date.

His is a malleable kind of masculinity; he looks like a crooner, a head boy, the guy at the fish and chip shop. He could be digging a hāngī or smoking a cigarette outside your literature class. We see him play with these tropes in his public image, through fashion, and incarnations of Marlon are clad in everything from white singlets and rugby jerseys to louche shirts and lean modish suits.

And then there’s that height and the youthful silliness, intact even at 34, which provides levity to the film. It’s brings an almost vaudevillian quality (unavoidable when you’re 6”3 and all limbs) to the shimmying through ‘My Boy’ video, and dancing across a pontoon for ‘Aua Atu Rā’. Bringing the latter song to life was pretty straightforward. “That one laid itself out,” he told me. “It’s about the ocean. But it’s also a meditative, confessional thing.” Other videos come from “flights of fancy” (I appreciate anyone who admits to these and does so with this turn of phrase, he dropped it twice). One of those fanciful flights was the retro, tracksuited ‘Rere Mai Ngā Rau’ — “I wanted to make a hip-hop video” — and it gives us yet another Marlon, this one wearing Fila and Oakleys.

He’s good at that video stuff, loves it in fact (it’s why he sidestepped into movies). For musicians, and everyone really, image is an increasingly big part of the job. Ours is a visually focused culture, and as a creative you have to channel a sense of the album and artist, cut through the noise and — if that’s your goal — communicate some authenticity (high-value currency right now). We’ve never been more aware of the thought and work that goes into image-making, the mechanics of the machine that goes into creating a star.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Lorde — she appears in the Marlon doco, during the Solar Power era — and her current look. The tape across her shoe had to have been intentional (everything is right?) and I spent more time than I should have trying, unsuccessfully, to find a shot of Mary Kate Olsen wearing duct-taped boots during the late 2000s — am I hallucinating that photo or do you remember it too? — so shall settle on referencing Blaze Foley’s instead. Beyond the boots, the fashion is loose, low-slung, unbothered, and it’s generating a sprawling word count of opinions. Liana Satenstein unpacked “low-res, L Word dressing” and the “freedom of a boring white shirt”; Rachel Tashjian took over Feed Me to explain some changes to Lorde’s creative team and what makes the return of our homegrown “pop auteur” actually, properly cool.

One of my group chats has been discussing the new era on and off for weeks, and the latest was the reveal of the new album. (I’d hoped she’d do something stealthy and weird on a Woolworths’ noticeboard; that idea is up for grabs, but I’ll take a commission). Lorde gave us a name, Virgin, a visual and a date, June 27. The cover art couldn’t be more different to Solar Power, but then again, all her albums have been. It’s disturbing, in a good way. It doesn’t get more intimate than an X-ray, and in this day and age, little is more personal — or loaded — than a pelvis.

From what she’s said about it so far, the album comes after a period of self-discovery and profound personal change (turn that kind of thing into music and you’ve usually got something pretty great) and she’s just delivered some revealing musing on selfhood for Document Journal.

Ella’s a master in the craft of self-mythology, and dividing her public self from the private. It’s critical. Mythmaking is interactive now, as artists act as both oracle and the shadows on the cave wall that followers interpret. How much should they keep from their public?

Speaking of image making, Auckland’s art people are well catered to this weekend, with not one but two fairs happening in Tāmaki Makaurau. (As a word “fair” has a bit of extra frisson to it, don’t you think?).

The sprawling Aotearoa Art Fair returns to the Viaduct Events Centre (and beyond its bounds) from May 1-4, with 49 galleries and 150 artists. I want to see the work from Nikau Hindin, Yuki Kihara, Peter Stichbury, Tui Emma Gillies, Jack Hadley, Monica Rani Rudhar and Yona Lee — plus whatever Art Paper editor Becky Hemus has selected from emerging artists for the Horizons section. Off-site, down at the thrusting silos, Public Record is hosting a free exhibition for five days, with work from Deborah Smith, and Kiriana O’Connell and more.

Fancy something more intimate? Also happening this weekend, up the hill and across Karangahape Road, the “gallery-led” May Art Fair is taking place in the gorgeous old Methodist Mission Hall. Coastal Signs’ Sarah Hopkinson and Michael Lett’s Andrew Thomas are spearheading it (Sally McMath is managing) and they aim to stimulate internationality and a “collegial spirit”. Saturday is free entry and Sunday is by appointment, and among the 15 exhibiting galleries are locals Grace and Sumer, and internationals SydneySydney, Lalia and Phillida Reid. I’m walking up there shortly to take a look today.

(I did wonder about crossovers, and Fine Arts Sydney and Auckland’s Season will have a presence at both fairs).

Two fairs at once? May is “conceived to complement the Aotearoa Art Fair” and intended to be additive to the weekend, and more boutique. Sarah, Andrew and Sally talk about their motivation in the current issue of Metro, worth a read for that and art writing by the sensational Samuel Te Kani.

This week I’ve been:

Celebrating… the launch of Sylvester’s new era, and collection, at Commercial Bay. It’s the first with Kate and Wayne’s sons Tom, Ike and Cosmo at the helm, and comes after unexpected challenges for the family, which Ike acknowledged gracefully in his speech to the crowd. And crowded it was: the store was packed — lots of the boys’ cool, young peers were there too, always good to see — and the till was ringing (someone even paid with a pile of fifties, long live the wallet). I was after the striped red hoodie, but so is everyone else, and the Sylvester-Conways told me a top-up is in the works.

Watching… Twin Peaks, because it’s been the weather for it.

Reading… Breakfast at Tiffany’s, which is far more grim than the film because the world is at war and Capote’s Holly is a teenager, but as a brisk novella-length read it’s great if you want to finish something. I’d like to see Gia Coppola or Sean Baker’s take on the material. Who would you cast though? They’d need a 1940s face and that shimmery edge that comes from fleeing nowhere good for big dreams. I’d go for Hunter Schafer or Emma Corrin, and for Paul it’s got to be Dominic Sessa.

Listening… to Kneecap, and the great new Viagra Boys album, Viagr Aboys.

Seeing… the darling scarves that Oosterom designer Nicole Hadfield has made for Hotel Indigo’s staff over lunch at Bistro Seine on the building’s ground floor. They’re printed with illustrations of Auckland architecture — sure to tickle the fancy of urbanists out there — and the pattern’s also on a pocket square and scrunchie. The city’s fashion crowd tucked into sourdough with whipped butter (this feels like a thing right now), assorted canapés and a very good chicken liver parfait at the launch, and since the hotel is the official accommodation partner for New Zealand Fashion Week I imagine we’ll see more of that come August.

Pencilling… a visit to Blue later next week, the elegant new all-day joint opening at that great spot top of Franklin Road. (I’ve been privy to a lot of info, and it sounds sublime). Go on Friday or during the weekend once they’ve had time to find their feet.

Wondering… when any of those trendy queezable olive oils will start landing on New Zealand shelves? Or are they here already? I predict we’ll see a local iteration from our homegrown FMCG disruptor, or from a small DTC brand with a story to tell. There are arguments for price (plastic is cheaper to make and ship than glass), usability and accuracy. Personally I heave a can; it’s weighty and cumbersome but, given the current price for this category, feels worth the effort. (Build some friction into your life where you can). I buy mine from Pita House in Pakuranga.

Did you know:

Sofia Coppola sent a bunch of Céline (two huge boxes apparently) to Jane Campion during the 2014 Cannes Film Festival?

Crushes on Karangahape Road does consignment now?

Ploughman’s lunch (my favourite) may predate girl dinner but it’s not as old as you’d expect?

The government has set up a school attendance dashboard (I hate all data dashboards) and there’s even a bar graph! Merging corporate performance metrics with surveillance culture and narc vibes, it would be crack-up in an Educators way if it didn’t feel so bleak.

New here? Catch up on Crust.

Enjoyed this? Like what I do? Why not become a paid subscriber, an annual subscription is less than a Graza starter kit (not that they ship to New Zealand anyway). If you’re already a subscriber, you can upgrade to paid via the browser version of Substack (not to mention Apple takes 30% commission on in-app purchases including subscriptions).

Ok Farro stocks squeezy olive oil now (thanks Zoe!).