Have you ever lost (and found) yourself in a dusty pile of the past?

Materialism > Consumerism.

Crust is a weekly newsletter on taste and culture from Tāmaki Makaurau.

In which I sort through 20 years worth of clothes, Tess packs up her life and leaves the country, and we discuss the difference between materialism and consumerism while walking down Dominion Road. There’s also a materially inclined exhibition, an imminent book set in 1980s Grey Lynn, and stray thoughts on Lorde’s resurrection.

Not to sound like a message filtered to your spam folder, but do you like touching things? I do. Cowhide suede, newsprint, Temuka pottery, felted wool (the best is accidental), old plastic school chairs, tussar silk, whatever they used to make steering wheels out of. And you know how that particular, perfect wooden spoon feels to use? Yeah, that.

A thesis could be written about why some materials are more satisfying than others (I’m sure someone has) but it’s all wildly subjective of course; I hate touching frosted glass, some people abhor the pile and nap of velvet. This material appreciation shapes the things that fill our homes — if you own a Moccamaster and have a spare $164.50 then Klay has just the thing for you and it's made from ‘roasted ash’, which I bet has good handfeel — and clothe our bodies. Confronting myself with the latter, I spent Easter weekend sorting through all the stuff I’ve accumulated (stashed would be a more honest turn of phrase) over the past 20 years, disemboweling cupboards and excavating storage. There’s things put away when I left home, when I left to go backpacking for two years, and when the pandemic left us in lockdown.

All these intimately personal relics serve as a time portal into past selves, and it was a trip. There’s the Zambesi pants I’d wear to Rakinos and D.O.C Bar; an assortment of silks from Miss Crabb that witnessed jugs of Hallertau at Golden Dawn; school uniforms; my graduate collection and another made the year after. Unearthing it all feels archeological. A Deadly Ponies bag bought during the brand’s early made-in-New-Zealand years looks better after a decade of improper storage, fatigued and grizzled (hot). I wondered how Hussein Chalayan felt after unburying his 1993 collection, and thought again about La Chimera, obsessed as it is with digging in the past for material objects and memories.

Continuous use also gives things character, with the patina of wear and time bestowing sense of life. There’s that human touch thing again, the flaws, and a tangible visibility of the past in a physical medium. It’s why freshly renovated villas look so unsettling, like new teeth in the face of an old suburb; the character that’s being protected is like Eliza Doolittle after Higgins gets his hands on her.

New Zealand has an affinity with vintage, born of necessity (economic, geographic) and a cultural valorisation of thrift, and there’s evolving cachet and class privilege at play too; a peeling old table reads differently in different households. Opshops are part of our national fabric and they’re everywhere, from good causes (SPCA, Hospice etc) to godly causes (church-run, the Salvos) and the many mythic tip stores (Aotea’s is cavernous). Many are catalogued by Collectors Anonymous, a savvy addition to any glove compartment.

This past time of trading our old stuff with each other may have shifted from newspaper classifieds to Trade Me and Facebook Marketplace, but nothing beats sifting through the stalls at Avondale Markets — I got my cast iron frying pan there — or Balmoral’s Central Flea. The latter will find you amongst throngs of cool, young Aucklanders, and you can witness the symbiotic nature of style at work (are they all wearing wide belts because they’re for sale, or are they for sale because they’re all wearing them?)

With the growing popularity of thrifting comes grumbles about higher prices, picked over stores and dwindling quality due to fast fashion donations. Those with a competitive nature might be inclined to keep a favorite spot secret, other’s value rarity and the thrill of the hunt. In last week’s newsletter vintage seller Juliet Stimpson pointed out the “vintage bro culture” of barn finds, and there are bragging rights that come with authenticity and a good origin story. (What do you say when people compliment your French chore jacket?)

What gets to be vintage and who gets to have it? Not everyone can hold onto things, or even have them in the first place — sometimes life makes you up sticks and leave, or serves you an itinerant existence — and some things slip in and out of our lives.

As with most Auckland flats, mine were furnished with second hand stuff, a medley of randomly acquired things that changed as the tenants did. My ‘grown up’ apartment now is full of old things too because I’m a pack rat with a propensity to hoard sentimental treasures and boring useful things (only one piece of furniture was bought factory new and it’s, predictably, the ubiquitous stool of Auckland).

Our lives surround people with a solar system of stuff — all the things we’ve carefully chosen, items that are thrust upon us, and those collected without a second thought. My Dad once told me we have to “live with our history” (while probably trying to foist an overly large chair on me) and I think about that a lot, because he’s right. It makes getting rid of things hard, that history, and I see it in other people’s things too, all those little ghosts on secondhand-store shelves and things that could be given a home. So practical! Such good quality! They just don’t make them like they used to!

Bemoaning our predilection for these good, old things and well aware of the pretensions of taste, Tess Nichol and I spent an afternoon a few weeks ago comparing materialism with consumerism while we walked down Dominion Road after an opshop drop off.

“That distinction between consumerism and materialism has been one that really lodged itself in my brain.” Her ex heard someone talking about it on RNZ and thought she’d want to hear it. “He was right,” Tess tells me as we rehash that conversation from the opposite sides of the globe (she’s in Canada now, the cause of the decluttering). “The argument they were making was that it could be positive to be materialist in the sense of really cherishing and looking after your material objects, as opposed to consumerist where you buy and discard a huge quantity of stuff.”

It was economist Richard Denniss, author of Curing Affluenza, making a case for materialism and kicking the habitual high of buying new stuff. He wanted people to find pleasure in what they already owned. That was 2017, an era of assurgent ethical-branding and rising awareness (Dana Thomas’ Fashionopolis came out in 2019) and years before the rise of Temu and Shein, but the essence of his argument still stands.

The theory stuck with Tess, who professes a love for beautiful objects, both practical and ornamental, and a “total weakness” for ceramic mugs. “I’d always felt vaguely guilty about that because it felt like it clashed with my values around wanting to consume less,” she tells me, and packing up her life came with a fresh wave discomfort when rehoming posessions. “I was embarrassed to find was actually almost painful, emotionally. I just love my stuff! But I like knowing it’s now with my friends living a new life where someone will care for and appreciate it.” (I took a puzzle and several books, telling myself I will indeed read the Dostoevsky. But will I?)

Amidst all the tariff fallout, Kyle Raymond Fitzpatrick questioned the prevailing culture of consumption and the side effects of “getting everything for nothing, of our becoming disconnected from human reality as we eschew a life for commercialism, for consumption”, pointing to some salient words from Naomi Klein. “We weren't born having to shop this much,” she said in 2014. “Late capitalism teaches us to create ourselves through our consumer choices: shopping is how we form our identities, find community and express ourselves.”

There’s a framework that helps with accumulation, and Tess deploys a simple criteria when buying things now: Will I use it, will I be able to take care of it, and does it feel special? “This might mean hard to find or one of a kind, well made, or particularly charming or beautiful, or made by hand by a local maker, second hand things are often most special because you feel you truly will never find them again.”

There’s a very real fear to that, a sense of scarcity, that maybe you’ll never see this thing again. (Will this be the last time I see that Braun coffee grinder in the wild?) I struggle to pass over woolen blankets, crockery and kitchenware, jeans and jumpers; underneath it is the knowledge that modern equivalents don’t clear the bar (‘enshitification’ applies to everything) and a fear that these things will go away entirely.

Reaching for the past via material things is mirrored by our visual media habits and the nostalgia paradigm. Is that why we like old Getty Images of celebrities? Do they gain a sense of rarity because that time is long gone? I was looking at photos from the early Met Galas (did you know Graydon Carter would sneak out early?) and they’re world’s away from the pageantry we can expect come May 5 — though I wonder if Anna’s managed to finally stamped out the smoking in the bathroom.

A fame relic that’s resurfaced on my algorithm this week is Princess Diana, and her public life and death are a case study in materialism and consumerism. Sean Monahan proposes that the old idea of celebrity — rarified, mysterious — is over; the media destroyed the British monarchy (American democracy is next) and Di was either destined or doomed. Frozen in time, she endures. Last year Shahzada Qasim wrote about the cross-cultural love for Diana and how she “intrinsically became a part of the Pakistani culture”.

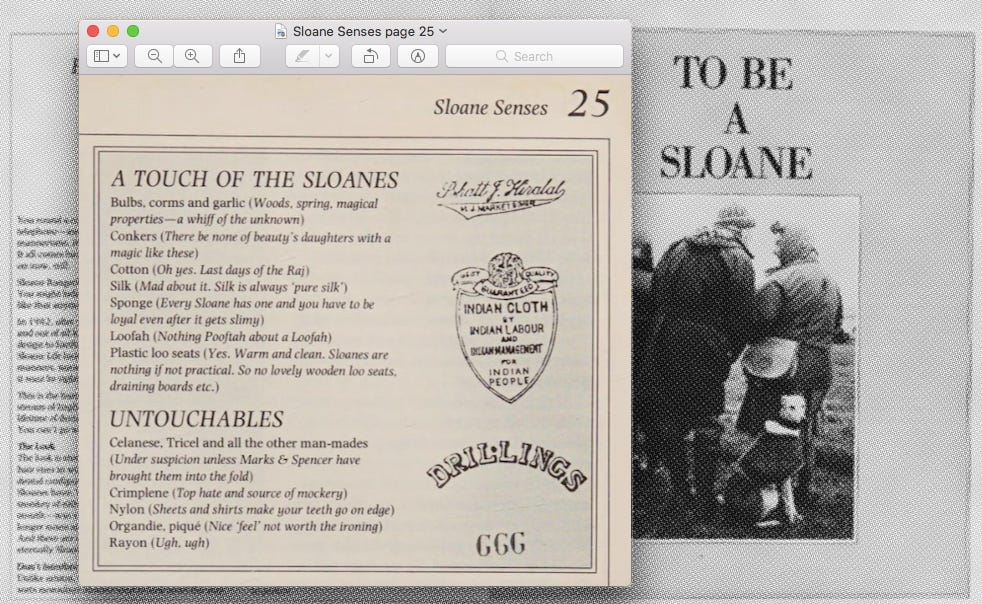

Her style outlived her, and it’s catalogued at length in 1982 book The Sloane Ranger Handbook, uncovered in pdf format by Kaitlin Phillips this week. Now that’s a group that went hard for old stuff. “Sloane Rangers love the past. You can’t have background without lashing of The Past. All the good things have been going for ages,” declare the book’s authors Ann Barr and Peter York in the ‘What Really Matters (in life)’ chapter. “It means old houses, old furniture, old clothes, old wine, old families, old money — everything lovey and faded and patina-ed and always been there.” According to the authors, when it comes to materiality Sloanes liked to touch conkers, cotton, sturdy glassware and “plastic loo seats”, but loathed crimplene, satin dressing gowns and mink.

And they loved a Barbour, which is currently making headlines for all sorts of reasons, proving context is everything (it’s worn by both Alexa Chung and Nigel Farage) and waxed cotton enjoys enduring appeal — Prada sent one down the runway last year.

This week I’ve been:

Listening… to ‘What Was That’, which reminds me of Melodrama, and includes references to backyards and MDMA (I would have been more euphemistic because acronymous drugs sound too corporate) and a more emo side of Lorde that we haven’t seen, musically, since before Solar Power. I’m so ready for the new album, appreciating the baggy fashion shift — that striped polo (it’s Balenciaga) is so North Shore noughties — and Dev Hynes dragging a speaker through Washington Square Park was brilliant.

Visiting… Objectspace on Rose Road with Zoe to see PUPURITIA. There’s quilt work by Tehani Ngapare Rau-Te-Tara Buchanan and Ngapare Poko Taua, a resplendent Ron Te Kawa piece, and something by Roka Hurihia Ngarimu-Cameron that I don’t want to spoil. It’s all gorgeous, moving and on until June 1st.

Reading… Dominic Hoey’s new book 1985. It’s set in Grey Lynn and released on May 6, so I’ll have more for you then.

Watching… Étoile on Prime Video. Amy Sherman-Palladino’s back with a new series, and it’s much less obnoxious than The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, and miles better than Bunheads. It tracks a transatlantic cast swap between Parisian Geneviève (Charlotte Gainsbourg, dialed up) from Le Ballet National, and New Yorker Jack (dashing Luke Kirby) of Metropolitan Ballet Theater — who I wish was wearing leather Lemaire flats instead of those white-soled sneakers. Because this is an ASP production there’s eccentric characters, affectations aplenty and lots of walk-and-talks. The stakes are high and this is silly, so I’m enjoying it so far. Gilmore Girls fans will be glad to see Yanic Truesdale back in the fold.

Trying… that coffee from Juno, finally, the Vienna, indulgently topped with sweet cream. As anyone who’s glanced at the Crust chat will know, I think it’s a treat worth the $11 expenditure (not every day though).

New here? Catch up on Crust.

Enjoyed this? Like what I do? Why not become a paid subscriber, a monthly subscription is less than an $11 coffee.

Dutch cast iron frypan in the free bin at hospice op shop…. Best thrifted score to date. I also keep an eye out for NZ wool anything.

Xx

Life’s irony’s the view we benefit

from physical, material delight

as though naught counts but what’s felt or in sight

while ignored our souls are desperate

for what should count the most—the infinite;

yet we’ll go on till it’s too late, despite

much instinct in us of what’s truly right

that life’s content is so inadequate.

.

Regardless, to that same life we cling tight

since the physical solely seems definite

thus for material matters we fight

—like the blind-mind addict’s barbiturate—

while Great Hereafter’s placed post-the-finite

so skewed are values foremost we’ll permit.